Japan has one of the world’s largest and most successful medical markets, with leading pharmaceutical companies including Eisai, Takeda, and Daiichi Sankyo, and medical device manufacturers like Terumo, NIPRO, and Hitachi Medico. As a founding member of the EU-US-Japan led International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceutical Use (ICH), Japan’s influence in the global medical industry is immense. Its influence is also unique, as Japan through its culture and methods of communication, particularly medical communication, sets itself apart from any other country, and making them a leader in the life sciences.

What are medical communications? The American Medical Writers Association (AMWA) defines medical communication as, “the development and production of materials that deal specifically with medicine or health care.” Such materials can include: journal articles and manuscripts for medical publications, continuing education materials, patient education brochures, regulatory documents for government agencies, grant proposals, marketing materials for pharmaceutical or medical device products, and more.

Communication in a medical setting can vary within cultures and geographies; as one of our previous blogs addressed, “Language itself is often a barrier when receiving treatment or communicating with health care practitioners, especially with an aging population.” Within Japan, the importance of recognizing the unique subcultures of individuals within the population is vital for adapting the medical communication style to be more patient centric, and improve overall patient care.

Another example of varying medical communications is outlined in this study which details physician-patient communication in Japan. Japanese physicians were found to have two different communication styles with patients, the first being a defined (more consistent and unchanging) style, and the second being an adaptive (more patient-centric, contextual) style. Physician communication with nurses was also evaluated, and similar variation was found between the two styles defined as individual (physician does not rely on the nurse to communicate with patient) and collaborative (physician relies on the nurse to foster communication with the patient).

With evidence for such diversity of communication within medicine in Japan, the importance of precise, unbiased written medical communication material fills a need for medical communications that transcend cultural interpretation. Transforming these materials can be a complex scientific process, depending on the language translated into, as well as the availability of certified, expert translators with medical expertise in Japan.

Japan is an interesting example for several reasons, including the high level of integration its medical firms experience in the global economy, as well as its uniqueness in domestic clinical policy. Individual Clinical Study Report (CSR) disclosure, for example, is widely becoming a globally-accepted requirement preceding journal publication, where in Japan it is not. However, for Japanese pharmaceutical firms who wish to expand their global market-share, they must prepare CSRs for global applications and disclosure. This interesting market niche for CSR translation and global preparation is further complicated by the immense sophistication of the written Japanese language. Clinical research employees who are both familiar with Japanese culture and fluent in Japanese as well as in English, for example, can be hard to find for some multinational CROs.

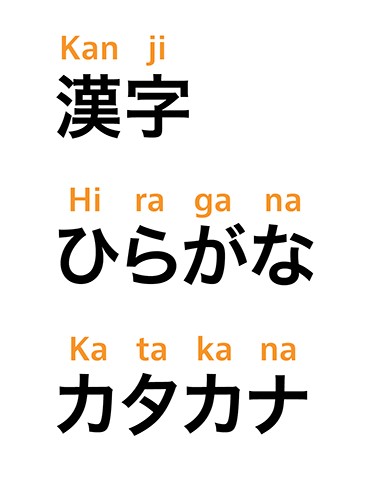

Written Japanese, accordingly, has been considered the most complicated written language in the world. As a Japanese blogger explained, Japanese is written in three different scripts, “From top to bottom: Kanji is mainly used for the lexical elements: nouns, verb stems, adjective stems, and so forth; Hiragana has rounded letter shapes, which are mainly used for the grammatical elements of sentences such as particles, auxiliary verbs, and suffixes of nouns; Katakana has an angular letter shape, which is most often used for foreign words and also for the purpose of emphasis.”

Most professional Japanese writing contains a combination of the scripts, depending on use. The use of one script or another depends on the setting used – cultural, scientific, and so on. While the situation can be further complicated by the decision to write horizontally (most commonly), or vertically (for specific uses), when it comes to medical communications, as in scientific writing, the horizontal orientation is preferred.

With so much base variation, the array of options for presenting material provides interesting and complex examples. Japanese newspapers, for example, show a combination of vertical and horizontal orientations in order to give the reader an optimal reading experience in their cultural context.

It is no surprise that expert medical linguists in Japan charge a higher fee per word in Japanese, than in other languages. However, with companies like Takeda reaching across their global capacities to develop a COVID-19 vaccine, the importance of conducting medical translation and writing to and from the Japanese language remains paramount. With Japan as a life science leader, and likely to remain so in the future, medical subject matter expert linguists will continue to be an integral role in healthcare. Although often challenging particularly in the life sciences, between the submission of CSRs, the complexity of the written language, and understanding the cultural nuances in terms of patient care, professional high-quality translation of Japanese is crucial in advancing the global healthcare ecosystem.